The Public Administration

SS Lieutenant Colonel Adolf Eichmann arrived in Hungary with an almost unsolvable task on the day of the German occupation, March 19, 1944. With his unit made up of a handful of men he was supposed to deport 760,000 to 780,000 Jews from a territory spanning 170,000 square kilometers. However, he received unexpected assistance from the newly appointed collaborating government that threw the whole Hungarian public administration system into action in order to plunder and deport Jews. Besides the effective operation of the gendarmerie and the police the precise and often enthusiastic work of thousands of notaries, constables, mayors, prefects and sub-prefects was needed to deport 430,000 people in only 56 days to the death factory of Auschwitz.

Click here to read more about the Holocaust in Hungary.

The Hungarian Public Administration and the Holocaust

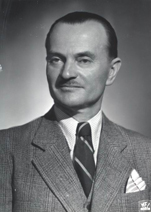

From late March 1944 the collaborating Sztójay government overwhelmed the country's Jewish population with a flood of restrictions. The practical implementation of antisemitic government decrees was left to local administrators (sub-prefects, mayors, constables, notaries, etc.). State Secretary of the Ministry of the Interior László Endre

|

State Secretary László Endre, the head of the public administration carrying out the ghettoisation and deportation |

At the local level, antisemitic ordinances were proclaimed by the leaders of the administration and (when required) these were carried out by law enforcement agencies (gendarmerie and the police). Implementation was supervised by the administrative body issuing the orders. As officials had to mediate government policy, they seemingly had little room to manoeuvre to follow their own judgment and influence events. This was far from the case, however. The attitude of local top administrators made a great difference in the weeks leading up to the deportation of Hungary's Jewish population. The administration had the option to carry out orders either causing various degrees of inconvenience, or acting humanely. The implementation of specific orders could be delayed and even sabotaged, as was attempted in some cases.

After the Jewish population was forced to wear a discriminating sign, segregation got under way. Based on a top-secret order issued April 7, 1944, the ghettoisation process started on April 16, 1944 first in Carpatho-Ruthenia and later across the entire country.[5] While, in contrast to Jewish quarters segregated for years, for instance, in Warsaw and Lublin, ghettos in the Hungarian countryside existed only a few weeks, but conditions in the days and weeks before deportation to Auschwitz proved to be crucial for residents.

The chances of survival of the Jews were affected by a number of single and combined factors: the location of the ghetto (set up

|

One of the entrances of the Új Street ghetto of Sopron is walled up |

The administrative apparatus in the DEGOB protocols

The DEGOB protocols clearly show that dispossessed Jews crammed into marked buildings, ghettos and collection camps came to realize that within certain limits, public officials enjoyed a measure of freedom and could greatly influence their fate.

The Notary of Nagykapos "was terribly hostile to the Jewish population. He caused us constant troubles."[6]

When the father and brother of E. L. from Técső were beaten at the town-hall by the gendarmes, "the local notary named Gajdics knew about it but did nothing to stop it; he did not like the Jews either".[7]

András Balázs from Királyhelmec "was a very cruel man. The population behaved decently, but the officials were vicious, they did not even talk to us".[8] "In Huszt, Chief Notary József Bíró was the most savage toward the Jews. He carried out all anti-Jewish orders without mercy."[9]

Following the German occupation, Béla Déri, a close associate of László Endre, was appointed to be mayor in Pestszentlőrinc. "He served the Germans to the last", remembered S. K.[10]

Even before the ghettoisation, the gendarmes beat the Jews savagely in Kövesdliget. The local notary always refused to extend any help to the Jews, "but he was eager to do us harm at any opportunity".[11]

In Perecseny, Notary Vladimir reported Jews who continued to ply their trade without license. These people were subsequently led

|

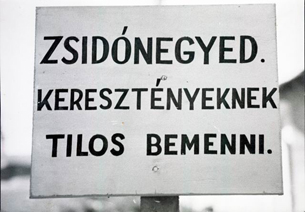

Sign at the entrance of the Zalaegerszeg ghetto (Jewish quarter. No entry for Christians) |

In Pestszenterzsébet the ghetto was set up in "buildings suffering the worst damage during the June bombings"".[13] (True, on the particularly hot summer of 1944 this made little difference, and the ghetto of Pestszenterzsébet was one of the least guarded.)

In Beregszász "civil servant Pál inspected the ghetto on several occasions and found the instituted measures too lax."[14]

According to the recollection of a survivor, the constable of Paks did not attempt to hide his attitude in respect to the matter, saying: "the day of the implementation of anti-Jewish measures was the most memorable of my career as a public servant." Accordingly, the ghetto in Paks presented an infernal sight. "We literally prayed for being locked into railway cars", remembered W. R.[15]

In the ghetto of Szatmárnémeti "all the Jews from the surrounding area were crammed in; we lived one on top of the other, in the courtyard and the attic".[16]

István Irányi, the chief notary of Szentmiklós, stole the most valuable part of Jewish assets. Subsequently, he provided information to gendarmes interrogating Szentmiklós Jews taken to the brick factory in Munkács as to which Jews may have had more money than already found. He singled out Sándor Kalus who was then forced to confess with the "help" of an axe handle.[17]

László Hajduk, the constable of Turz was also familiar with the financial status of Jews taken to the ghetto in Nagyszőllős and provided names to gendarmes searching the place for valuables. "Based on his information a new wave of searches and interrogation started for cash and other valuables, naturally accompanied by the most brutal physical abuse.[18]

This is how E. L. from Alsóapsa remembered the leading official of the village: "Mihály Phillip lives in our minds as ... an evil person."[19]

Jews taken to the Ungvár ghetto from Szenteske did not escape the reach of their antisemitic constable, who filed

[20] Survivors of the Ungvár ghetto all condemned the actions of the city's Mayor László Megay.[21]According to the testimony of N. R., a seamstress from Kisapsa, "the local notary was very wicked, he did not like Jews"[22]

The constable acted as the civilian commander of the ghetto in Szamosudvarhely. "He came to the ghetto every day with a Hungarian-speaking SS officer; he regularly ordered people to be tied up and tortured by different means."[23]

This is how B. S. described the behaviour of Huszt Chief Notary József Bíró during ghettoisation: "He behaved worse than the SS ... he came to the ghetto and robbed us of the little food we had left".[24]

Based on the DEGOB protocols, the overall picture painted of the state administration is overwhelmingly negative, although it is

|

Regent Miklós Horthy |

In the course of just a few weeks, hundreds of thousands of people were locked in ghettos and collection camps where they languished under horrific conditions and treatment before being deported to Birkenau in the quickest operation in the history of the Holocaust. All of this would not have been possible without the active cooperation of many thousands of Hungarian civil servants of all ranks; by performing their daily duties, they kept in motion the official mechanism set up for a state-organized "dejewification" program.

Footnotes

[1] Braham 1997, p. 416.

[2] Veesenmayer wrote to the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs: "I emphatically demanded the replacement of prefects and sub-prefects with a negative attitude and I received assurances that within eight days we can expect to see the dismissal of 8 to 10 such persons. In view of the special urgency of the case I will apply constant pressure to get quick results." Juhász et al. 1968, p. 824.

[3] This is what Baron János Jósika (Szilágy County) and Count Béla Bethlen (Szolnok-Doboka County) did. Braham 1997, p. 423.

[4] Ránki 1978, p. 164.

[5] Braham 1997, p. 1347.

[6] Protocol 656.

[7] Protocol 404.

[8] Protocol 393.

[9] Protocol 2539.

[10] Protocol 661.

[11] Protocol 1583.

[12] Protocol 1859.

[13] Protocol 2248.

[14] Protocol 443.

[15] Protocol 3526.

[16] Protocol 1584.

[17] Protocol 1358.

[18] Protocol 45.

[19] Protocol 110

[20] Protocol 1217.

[21] See, for example, Protocols 88, 666, 1750 and 1743. About Megay, see also Braham 1997, pp. 566-567.

[22] Protocol 1781

[23] Protocol 2593.

[24] Protocol 28. On József Bíró's actions in the ghetto, see also Protocol 969.

References

Braham 1997

Randolph L. Braham: A népirtás politikája - a Holocaust Magyarországon. (The Politics of Genocide. The Holocaust in Hungary.) Vols. 1-2. Budapest, 1997, Belvárosi Könyvkiadó.

Juhász et al. 1968

Gyula Juhász - Ervin Pamlényi - György Ránki - Loránt Tilkovszky (eds.): A Wilhelmstrasse és Magyarország. Német diplomáciai iratok Magyarországról 1933-1944. .(The Wilhelmstrasse and Hungary. German Diplomatic Documents on Hungary. 1933-1944.) Budapest, 1968, Kossuth.

Ránki 1978

György Ránki: 1944. március 19. (March 19, 1944.) Budapest, 1978, Kossuth.